It was sometime in the mid-80’s that I became briefly obsessed with Bigfoot, or as (s)he is more formally known, Sasquatch. I’d like to think that a recent viewing of Harry and the Henderson’s—which is by far the best of the major-studio productions about Bigfoot—didn’t have anything to do with this brief but intense obsession, but more than likely it did.

At the time, I was around seven or eight, and my grandfather lived in a secluded part of Whidbey Island, a sparsely populated,168-square mile stretch of land about 30 minutes north of Seattle.

Every time I visited Grandpa Jamie on the island, I’d look forward to the long drive from the ferry terminal through woods filled with tall evergreens stretching miles and miles, as far as my little eyes could see, to his big house overlooking the water.

As we drove through those woods, I’d get lost in my mind, contemplating their depths, peering through the rough, brown spears shooting up through ground covered in dead pine needles, whizzing by at sixty miles per hour.

What was in there? What amazing things were hidden just beyond my sight? What mysteries were waiting to be discovered?

I was convinced that Bigfoot lived on Whidbey Island, and I believed, each and every time I drove to grandpa’s house, that this would finally be the time that I’d see the great, lumbering brute stomping through the woods.

My parents told me that the search was futile. “You won’t find Bigfoot in there,” they said. “Because Bigfoot doesn’t exist.”

I knew they were wrong, of course. Adults most always were.

Grandpa Jamie took a different approach. “Those woods aren’t big enough for Bigfoot,” he told me. Most likely Bigfoot lived in the Cascades, not on an island in the Puget Sound.

My weekends at Grandpa Jamie’s house were magical. An architect by trade, he had designed and built a beautiful modernist-inspired home that was perched on a cliff overlooking Cultus Bay.

I’d spend hours peering out the huge triangle-shaped windows, using binoculars to explore the vast view. Across the bay, little houses along Sandy Hook Drive dotted the coast line, and I’d spy on the families that lived there, wondering what life was like on the side of the bay.

When the tide was out, Cultus Bay turned into a vast, sea-water-soaked sand flat filled with Geoducks. From my view, I could watch through my binoculars as families ventured out with plastic buckets and shovels to collect the tasty morsels left behind in the tide pools.

On days when the sun came out, Grandpa Jamie would take me down to the sand flats to collect clams too. Later that night, we’d cook them up and eat them out on his deck and then go for a soak in his hot tub.

In the evenings, and on rainy days, I’d venture to the basement, where all manner of treasures were to be found—an old trumpet, vast collections of Louis L’amour books, baseball gloves, and puppets—and watch Disney movies on VHS with Grandpa’s expansive drafting desk behind me in what made up his home studio.

I’ve recently been thinking a lot about those lost days on Whidbey Island. Much has been lost since then. After his wife died years ago, Grandpa Jamie sold the house and went down to warmer climates in California. The memories from those times are like ghosts, seeming so tangible but like waifs appearing in the corner of my mind’s eye, dissipating when I try to grasp them.

The wonder is gone too. As a child, the island seemed so vast and full of wondrous possibility. Today, it’s just another beautiful, yet remote location. I know there are no mythical beasts tromping through its forests. The people living across the bay on Sandy Hook Drive are just normal folk with lives that are probably as mundane as mine. There is no more mystery, and very few days dedicated to discovery.

Now, I have children of my own, two young boys who have taken up the torch of imagination. For them, the world is still full of things to explore, and anything is possible—until they learn (or are told) it’s not.

As a creative, I’ve begun to feel my loss of child-like wonder and innocence more acutely. I solve problems for a living, but often I find myself not wondering what’s possible but instead drawn to the concrete. There are no Bigfoot in those woods.

But, what if there are?

Watching the way my boys play and seeing how their minds make connections between reality and fantasy, I’ve begun to hunger again for a time when I didn’t start with reality but instead with wonder.

The fascinations of my childhood, the Bigfoots and the like, were beautiful because they were mysterious. I didn’t feel the need to solve the mysteries but instead to enjoy them. In the mysterious, anything was possible. You couldn’t prove it…and you couldn’t not prove it. So you were free to create and imagine.

As creatives, I think there’s something valuable in being able to step back in time a bit and rediscover mystery and mythos. And I believe the best brands do this.

For instance, the Nike “Find Your Greatness” campaign was all about what’s possible, and with beautiful, almost poetic words and images, Nike makes us feel again like that kid who can make the high dive, do a slam dunk, and run a marathon.

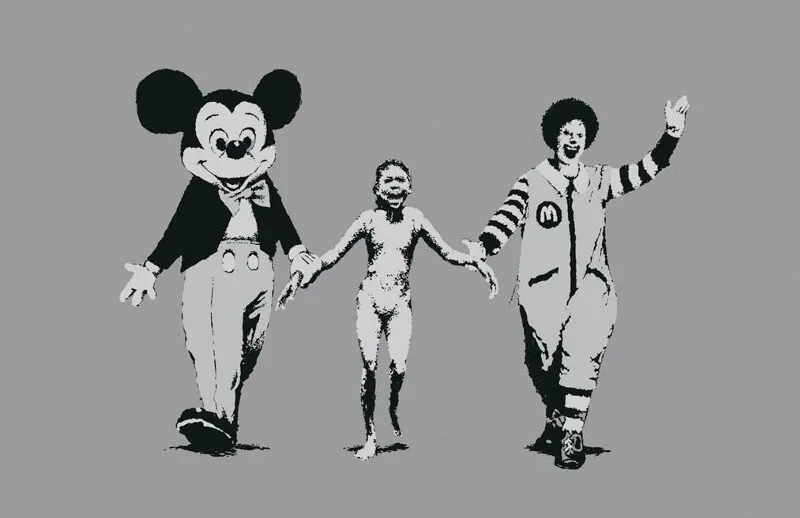

Or take the work of Banksy. Who, like a child, sees beyond the wall to a canvas of possibilities.

And whose work is often a bitter commentary on lost and commandeered innocence by societies bent on ruthlessly destroying beauty and creativity—and even how those societies use child-like wonder to profit.

In the end, it would profit us well as creatives to step back from profits and rediscover beauty and meaning and story and mythos and mystery.

When we do, what we have lost can be rediscovered. Much like I dug up the memories of my childhood as I wrote this essay, and like I dug up Geoducks from the sand flats of Cultus Bay when the tide rolled out.

I’ve poignantly learned this as a father: I can either foster creativity and wonder in my children, “Those woods aren’t big enough,” or I can stamp it down, “Big Foot doesn’t exist.” One beckons them to grow-up—the other to think bigger. As creatives, we wield the same power for the world, and for ourselves, if we take the time to stop and look and dream.